As promised, I hunted for and found the article regarding “what would happen”. Here it is:

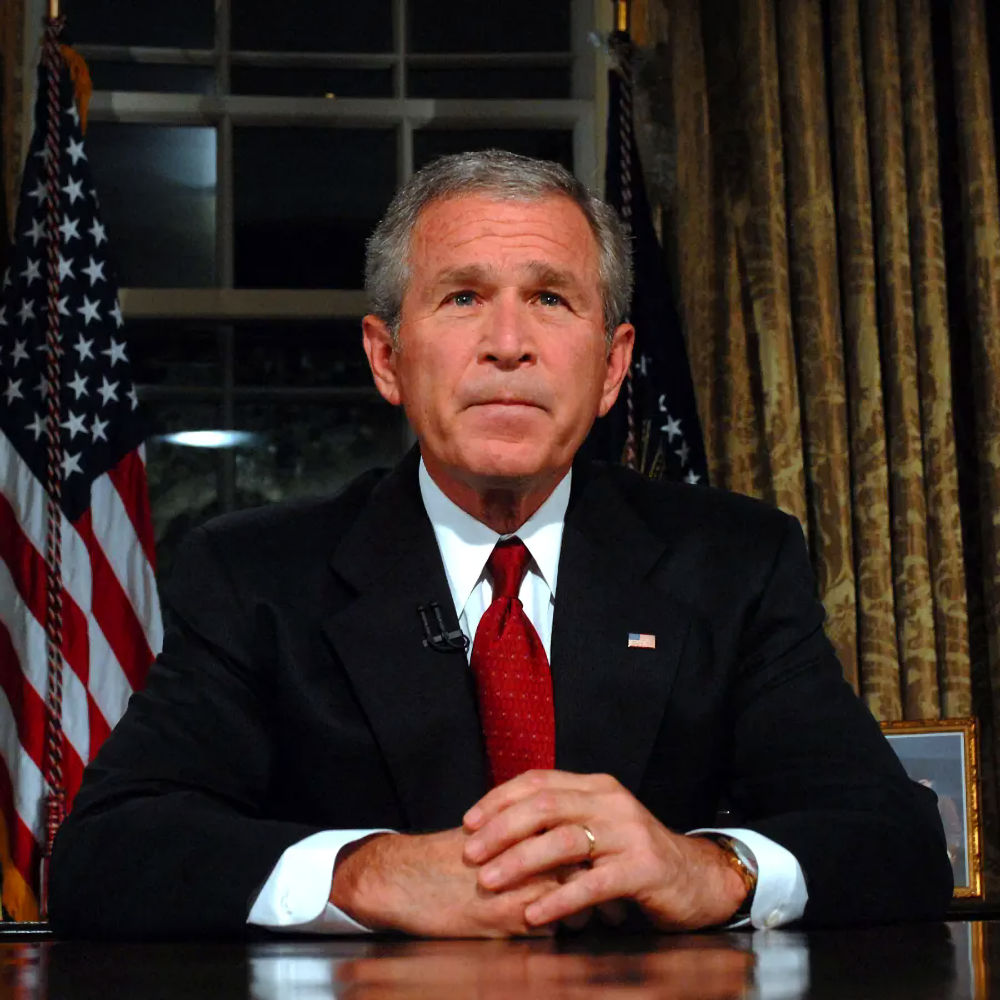

Held up by a Secret Service bodyguard in his dying moments after being shot in the stomach, this is President Bush being assassinated.

The American leader is surrounded by a crowd of panicking onlookers just seconds after being gunned down by a Syrian-born U.S. citizen outside a Chicago hotel.

But this shocking image, created by putting the President’s face onto an actor with digital wizardry, is part of a new British drama for Channel Four about the War on Terror.

In Death Of A President, which has caused outrage in America and will premiere at the Toronto Film Festival this month, the shooting is a starting point for a fictional documentary about what happened next. So what would happen if President Bush was assassinated?

Here, a historian looks to the future and imagines the terrifying consequences.

BEFORE that fateful day – November 9, 2006 – historians liked to say the world could never again lurch into global crisis because of one man’s death, as it had in 1914 when Austria’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand was murdered in Sarajevo, sparking World War I.

The assassination of John Kennedy at the height of the Cold War hadn’t led to Armageddon in 1963, so why should things spiral out of control now if a president was murdered? That confident view was shattered as global communications networks froze from overload while transmitting round the world the picture of the 43rd President of the United States slumping forward after being fatally shot in the stomach.

The murder of George W. Bush set off a global crisis with which we still live today, ten years after he was killed.

Of course, in retrospect, we historians could see it all coming. In the summer of 2006, there had been the ‘proxy war’ between America and Iran fought out in Lebanon between their two regional allies, Israel and Hezbollah. That war ended badly for Israel and emboldened Iran to defy the United Nations and, more to the point, the United States over its nuclear ambitions.

George W. Bush’s hopes of bringing ‘peace through democracy’ to the Middle East after his invasion of Iraq had already worn thin by autumn 2006. Anti-war demonstrations had become more numerous and security tightened everywhere.

The crude dum-dum bullet fired into the President’s stomach that November day caused fatal bleeding and the media were reporting the suspected assassin’s details within minutes.

Few people in America needed to know more than that the suspected killer of their President was Syrian-born. As the spotlight of blame focused on Syria, regarded by Americans as Iran’s poodle, the Iranian Foreign Ministry didn’t help its cause by issuing a perfunctory statement expressing regret that the President had ‘died in a violent manner’ and hoping that the American people would soon choose a new one who would be more peace-loving.

It outraged Americans and George W’s mother Barbara was overheard at the state funeral telling Cherie Blair: ‘It was like what you say to the maid when her dog gets run over. Get a new one, dear, you’ll get over it.’

The American public wasn’t interested in the formal regrets from Damascus and Tehran. Television coverage showed scenes of jubilation on the streets of Syrian and Iranian cities.

The new President, speaking from a ‘secure location’ soon nicknamed Bunker One, announced that ‘those who celebrate death will learn to taste it soon enough’. Dick Cheney appeared unfazed by the day’s gruesome events.

While America closed ranks and mourned, across the Islamic world Bush’s death was greeted with outpourings of joy. American troops in Iraq and Afghanistan got into firefights with local militias shooting in the air. Saddam’s trial was suspended as the defendants hugged each other in the dock.

But what hurt Americans most was the Europeans’ lack of grief. Officially, Europe, from Brussels to Berlin and Paris, expressed sorrow and outrage, and President Chirac led the EU mourners in Washington.

But there was nothing like the sadness which greeted Kennedy’s murder four decades earlier.

Despite Britain’s own experience of Islamic terrorism, the public response to the murder of the American president here was muted, at best; and in some quarters, not all Muslim, it was joyful.

The Independent newspaper published its obituary with a front-page collage under the headline ‘Latest victim of war on terror’.

A passport-style photograph of the late President was put in alphabetical order between a Marine sergeant, George Urban Bush, killed in Iraq the day before and an Air Force pilot, Ryan Caldwell, killed in a helicopter crash near Kabul on the same day the President was shot.

The BBC played a montage of Bush’s malapropisms from ‘Don’t mis-underestimate me’ to ‘The nostalgia for my administration will only begin after it’s over’.

The book of condolence at the U.S. embassy in London was thin, though the ambassador diplomatically put the short queue waiting to sign down to ‘fear of a terrorist attack’.

At home and abroad, the gloating over Bush’s death soon gave way to a sober realisation that he had actually been a check on Dick Cheney’s ruthless way of defending America from enemies at home or abroad.

Executive orders authorising detention without trial of citizens as well as aliens suspected of ‘terrorist affiliations’ and closing America’s borders were signed off with astonishing alacrity, as were military plans to strike regimes that had celebrated Bush’s death.

Syria was attacked, but Iran bore the brunt. Mass strikes by bombers and cruise missiles knocked out any capacity Iran had for making modern weapons, let alone nuclear bombs, but at a huge price. A country of 70million cowered under the shadow of burning oil wells and the pollution from devastated petro-chemical plants.

Fighting Iran turned out to be much bloodier than the blitzkrieg against Saddam’s Iraq.

Iran’s Revolutionary Guards had learned the lessons of Hezbollah’s war with Israel. They avoided head-on confrontation with the U.S. Army’s armoured columns. Ambush and sabotage were their weapons.

A grim war went on year after year in the lunar landscape which was much of Iran. As America struggled to find a replacement for the Ayatollahs’ regime, even the willing support of Iranian migrants from America wanting to wipe away the stain of the assassin’s crime could not build a stable pro-U.S. government in Tehran.

In Britain, America’s strike against Iran set off protests from East London to Yorkshire. Islamic radicals declared emirates in Blackburn and Bradford. Petrol bombs flew as the police tried to restore order.

Tony Blair decided he couldn’t retire in a crisis. Instead David Cameron’s Tories joined him in a National Government as endemic disorder in some urban areas was compounded by a dramatic increase in attacks on British troops in Basra and in parts of Afghanistan.

When Tony Blair stepped down in 2009 to join President Cheney’s Anti-Assassination Commission, it was David Cameron who won the election, attacking Gordon Brown as out of touch with a world in crisis.

Oil prices went on climbing steadily, and no one needs reminding that petrol today is still £3 a litre here and that David Cameron’s ‘green is the colour of national security’ government only lets you buy 30 litres a week.

But for America, it was crises closer to home following George Bush’s murder that shaped events.

Donald Rumsfeld at the Pentagon ‘Those who celebrate death will learn to taste it soon enough’ A grim war went on year after year in Iran seemed rejuvenated.

Even as U.S. planes and cruise missiles struck at targets across Iran, American naval power went into action against Iran’s ally Hugo Chavez, the President of Venezuela. A wave of protests swept Latin America. Chaos engulfed much of Mexico, sending waves of refugees north to the American border.

US troops tried to keep them out and ‘suspect types’ were shipped to Guantanamo Bay for screening.

The Guantanamo Bay camp was enlarged to accommodate the internees. Castro’s regime protested. The ailing Fidel wasn’t really in charge any more and his brother, Raul, tried to boost his own public image by organising a mass march to the U.S. base.

Whatever the younger Castro meant to happen, the carefully orchestrated crowds began to pull at the fences around the camp and then to try to climb it.

What happened next is disputed. The U.S. Marines guarding the camp claimed Cuban secret policemen shot at the people trying to climb into the base to stop them escaping from communism. The Cuban authorities said their security forces opened fire to defend the protesters, who were being attacked by the Yankee soldiers. Soon 113 people, including women and children, were dead.

The ‘Guantanamo Massacre’ provoked outrage in Havana. Cheney told Rumsfeld to ‘swat’ Castro’s regime once and for all. Another war of liberation broke out.

The backlash from these attempts to resolve America’s foreign problems with decisive military strikes overshadowed the domestic impact of Bush’s death. Iranian and Arab Americans weathered the wave of revenge pogroms set off by the assassination, but the bureaucracy of Homeland Security extended its surveillance over them, and pretty well anyone else.

Cheney’s re-election campaign in 2008 was conducted in a virtual state of emergency, with him addressing the Republican convention by 3D video link from a secure location. The mood of ongoing crisis, combined with the choice of Jeb Bush as his Vice President, widely seen in America as a tribute to the slain President, ensured him a landslide.

For a man with a history of heart problems, Cheney’s survival for almost ten years as president during what the New York Times called ‘Our Time of Troubles’ was remarkable.

‘I thrive on crisis,’ Cheney explained, ‘it was peace that got me tense.’ Occasionally he was short of breath, but Cheney even turned this to his advantage. Images of President Cheney in a wheelchair at Thanksgiving 2010 were carefully choreographed to recall Franklin Roosevelt in charge of the war effort 70 years earlier.

Despite the mayhem since Bush’s murder, most Americans had preferred to stick by Dick Cheney. His no-nonsense manner reassured, even as crises kept recurring.

For an embattled America and its allies, this endless war, with its relentless suicide bombings, anarchy in countries all over the globe and brutal reprisals, became known as a ‘clash of civilisations’. But how much worthy of the name civilisation remained to be defended?